![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Frederick Douglass was a former slave who became a highly respected author, orator, and statesman. Before the Civil War, he was a

prominent figure in the

abolitionist movement; after the war, he continued to work for equality and eventually held a number of high offices,

including ambassador to Haiti, under five different presidents. His first autobiography Narrative

of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), covering his early life and escape to freedom, is one of the most famous American slave narratives.

At the 1893 Columbian Exposition, Haiti, the only

black nation with its own pavilion, let the elderly Douglass and the young activist Ida B. Wells and others use its pavilion as a

platform for distributing their protest pamphlet "The Reason Why

the Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition." In it they observed that "Theoretically open to all Americans, the Exposition practically is, literally and figuratively, a

'White City,' in the building of which the Colored American was allowed no helping hand, and in its glorious success he has no share."

![]()

![]()

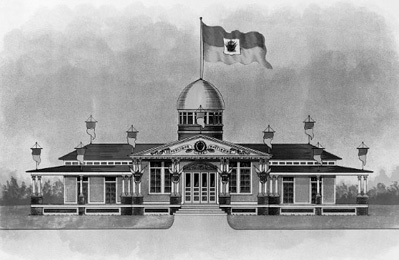

Pavilion of the Republic of Haiti at the World's

Exposition 1893--artist

unknown.

The colored people of America are not indifferent to the good opinion of the world, and we have made every effort to improve our first years of

freedom and citizenship. We earnestly desired to show some results of our first thirty years of acknowledged manhood and womanhood. Wherein we have

failed, it has been not our fault but our misfortune, and it is sincerely hoped that this brief story, not only of our successes, but of trials and

failures, our hopes and disappointments will relieve us of the charge of indifference and indolence. We have deemed it only a duty to ourselves, to make

plain what might otherwise be misunderstood and misconstrued concerning us. To do this we must begin with slavery. The duty undertaken is far from

a welcome one.

It involves the necessity of plain speaking of wrongs and outrages endured, and of rights withheld, and withheld in flagrant contradiction to boasted

American Republican liberty and civilization. It is always more agreeable to speak well of one's country and its institutions than to speak otherwise;

to tell of their good qualities rather than of their evil ones.

There are many good things concerning our country and countrymen of which we would be glad to tell in this pamphlet, if we could do so, and at the same

time tell the truth. We would like for instance to tell our visitors that the moral progress of the American people has kept even pace with their

enterprise and their material civilization; that practice by the ruling class has gone on hand in hand with American professions; that two hundred

and sixty years of progress and enlightenment have banished barbarism and race hate from the United States; that the old things of slavery have entirely

passed away, and that all things pertaining to the colored people have become new; that American liberty is now the undisputed possession of all the

American people: that American law is now the shield alike of black and white; that the spirit of slavery and class domination has no longer any

lurking place in any part of this country; that the statement of human rights contained in its glorious Declaration of Independence, including the

right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness is not an empty boast nor a mere rhetorical flourish, but a soberly and honestly accepted truth,

to be carried out in good faith; that the American Church and clergy, as a whole, stand for the sentiment of universal human brotherhood and that its

Christianity is without partiality and without hypocrisy; that the souls of Negroes are held to be as precious in the sight of God, as are the souls of

white men: that duty to the heathen at home is as fully recognized and as sacredly discharged as is the duty to the heathen abroad; that no man on

account of his color, race or condition, is deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law; that mobs are not allowed to supercede

courts of law or usurp the place of government; that here Negroes are not tortured, shot, hanged or burned to death, merely on suspicion of crime and

without ever seeing a judge, a jury or advocate; that the American Government is in reality a Government of the people, by the people and for the

people, and for all the people; that the National Government is not a rope of sand, but has both the power and the disposition to protect the lives

and liberties of American citizens of whatever color, at home, not less than abroad; that it will send its men-of-war to chastise the murder of its

citizens in New Orleans or in any other part of the south, as readily as for the same purpose it will send them to Chili, Hayti or San Domingo; that

our national sovereignty, in its rights to protect the lives of our American citizens is ample and superior to any right or power possessed by the

individual states; that the people of the United States are a nation in fact as well as in name; that in time of peace as in time of war, allegiance

to the nation is held to be superior to any fancied allegiance to individual states; that allegiance and protection are here held to be reciprocal;

that there is on the statute books of the nation no law for the protection of personal or political rights, which the nation may not or can not enforce,

with or without the consent of individual states; that this World's Columbian Exposition, with its splendid display of wealth and power, its triumphs

of art and its multitudinous architectural and other attractions, is a fair indication of the elevated and liberal sentiment of the American people,

and that to the colored people of America, morally speaking, the World's Fair now in progress, is not a whited sepulcher.

All this, and more, we would gladly say of American laws, manners, customs and Christianity. But unhappily, nothing of all this can be said, without

qualification and without flagrant disregard of the truth. The explanation is this: We have long had in this country, a system of iniquity which

possessed the power of blinding the moral perception, stifling the voice of conscience, blunting all human sensibilities and perverting the plainest

teaching of the religion we have here professed, a system which John Wesley truly characterized as the sum of all villanies, and one in view of which

Thomas Jefferson, himself a slaveholder, said he "trembled for his country" when he reflected "that God is just and that His justice cannot sleep

forever." That system was American slavery. Though it is now gone, its asserted spirit remains.

The writer of the initial chapter of this pamphlet, having himself been a slave, knows the slave system both on the inside and outside. Having studied

its effects not only upon the slave and upon the master, but also upon the people and institutions by which it has been surrounded, he may therefore,

without presumption, assume to bear witness to its baneful influence upon all concerned, and especially to its malign agency in explaining the present

condition of the colored people of the United States, who were its victims; and to the sentiment held toward them both by the people who held them in

slavery, and the people of the country who tolerated and permitted their enslavement, and the bearing it has upon the relation which we the colored

people sustain to the World's Fair. What the legal and actual condition of the colored people was previous to emancipation is easily told.

It should be remembered by all who would entertain just views and arrive at a fair estimate of our character, our attainments and our worth in the scale

of civilization, that prior to the slave-holder's rebellion thirty years ago, our legal condition was simply that of dumb brutes. We were classed as

goods and chattels, and numbered on our master's ledgers with horses, sheep and swine. We were subject to barter and sale, and could be bequeathed and

inherited by will, like real estate or any other property. In the language of the law: A slave was one in the power of his master to whom he belonged.

He could acquire nothing, have nothing, own nothing that did not belong to his master. His time and talents, his mind and muscle, his body and soul, were

the property of the master. He, with all that could be predicated of him as a human being, was simply the property of his master. He was a marketable

commodity. His money value was regulated like any other article; it was increased or diminished according to his perfections or imperfections as a beast

of burden.

Chief Justice Taney truly described the condition of our people when he said in the infamous Dred Scott decision that they were supposed to have no

rights which white men were bound to respect. White men could shoot, hang, burn, whip and starve them to death with impunity. They were made to feel

themselves as outside the pale of all civil and political institutions. The master's power over them was complete and absolute. They could decide no

question of pursuit or condition for themselves. Their children had no parents, their mothers had no husbands and there was no marriage in a legal

sense.

But I need not elaborate the legal and practical definition of slavery. What I have aimed to do, has not only been to show the moral depths, darkness

and destitution from which we are still emerging, but to explain the grounds of the prejudice, hate and contempt in which we are still held by the

people, who for more than two hundred years doomed us to this cruel and degrading condition. So when it is asked why we are excluded from the World's

Columbian Exposition, the answer is Slavery.

Outrages upon the Negro in this country will be narrated in these pages. They will seem too shocking for belief. This doubt is creditable to human

nature, and yet in view of the education and training of those who inflict the wrongs complained of, and the past condition of those upon whom they

were inflicted as already described, such outrages are not only credible but entirely consistent and logical. Why should not these outrages be

inflicted?

The life of a Negro slave was never held sacred in the estimation of the people of that section of the country in the time of slavery, and the abolition

of slavery against the will of the enslavers did not render a slave's life more sacred. Such a one could be branded with hot irons, loaded with chains,

and whipped to death with impunity when a slave. It only needed be said that he or she was impudent or insolent to a white man, to excuse or justify

the killing of him of her. The people of the south are with few exceptions but slightly improved in their sentiments towards those they once held as

slaves. The mass of them are the same to-day that they were in the time of slavery, except perhaps that now they think they can murder with a decided

advantage in point of economy. In the time of slavery if a Negro was killed, the owner sustained a loss of property. Now he is not restrained by any

fear of such loss.

The crime of insolence for which the Negro was formerly killed and for which his killing was justified, is as easily pleaded in excuse now, as it was

in the old time and what is worse, it is sufficient to make the charge of insolence to provoke the knife or bullet. This done, it is only necessary to

say in the newspapers, that this dead Negro was impudent and about to raise an insurrection and kill all the white people, or that a white woman was

insulted by a Negro, to lull the conscience of the north into indifference and reconcile its people to such murder. No proof of guilt is required. It

is enough to accuse, to condemn and punish the accused with death. When he is dead and silent, and the murderer is alive and at large, he has it all

his own way. He can tell any story he may please and will be believed. The popular ear is open to him, and his justification is sure. At the bar of

public opinion in this country all presumptions are against the Negro accused of crime.

The crime to which the Negro is now said to be so generally and specially addicted, is one of which he has been heretofore, seldom accused or supposed

to be guilty. The importance of this fact cannot be over estimated. He was formerly accused of petty thefts, called a chicken thief and the like, but

seldom or never was he accused of the atrocious crime of feloniously assaulting white women. If we may believe his accusers this is a new development.

In slaveholding times no one heard of any such crime by a Negro. During all the war, when there was the fullest and safest opportunity for such assaults,

nobody ever heard of such being made by him. Thousands of white women were left for years in charge of Negroes, while their fathers, brothers and

husbands were absent fighting the battles of the rebellion; yet there was no assault upon such women by Negroes, and no accusation of such assault.

It is only since the Negro has become a citizen and a voter that this charge has been made. It has come along with the pretended and baseless fear

of Negro supremacy. It is an effort to divest the Negro of his friends by giving him a revolting and hateful reputation. Those who do this would make

the world believe that freedom has changed the whole character of the Negro, and made of him a moral monster.

This is a conclusion revolting alike to common sense and common experience. Besides there is good reason to suspect a political motive for the charge.

A motive other than the one they would have the world believe. It comes in close connection with the effort now being made to disfranchise the colored

man. It comes from men who regard it innocent to lie, and who are unworthy of belief where the Negro is concerned. It comes from men who count it no

crime to falsify the returns of the ballot box and cheat the Negro of his lawful vote. It comes from those who would smooth the way for the Negro's

disfranchisement in clear defiance of the constitution they have sworn to support – men who are perjured before God and man.

We do not deny that there are bad Negroes in this country capable of committing this, or any other crime that other men can or do commit. There are bad

black men as there are bad white men, south, north and everywhere else, but when such criminals, or alleged criminals are found, we demand that their

guilt shall be established by due course of law. When this will be done, the voice of the colored people everywhere will then be "Let no guilty man

escape." The man in the South who says he is for Lynch Law because he honestly believes that the courts of that section are likely to be too merciful

to the Negro charged with this crime, either does not know the South, or is fit for prison or an insane asylum.

Not less absurd is the pretense of these law breakers that the resort to Lynch Law is made because they do not wish the shocking details of the crime

made known. Instead of a jury of twelve men to decently try the case, they assemble a mob of five hundred men and boys and circulate the story of the

alleged outrage with all its concomitant, disgusting detail. If they desire to give such crimes the widest publicity they could adopt no course better

calculated to secure that end than by a resort to lynch law. But this pretended delicacy is manifestly all a sham, and the members of the blood-thirsty

mob bent upon murder know it to be such. It may deceive people outside of the sunny south, but not those who know as we do the bold and open defiance

of every sentiment of modesty and chastity practiced for centuries on the slave plantations by this same old master class.

We know we shall be censured for the publication of this volume. The time for its publication will be thought to be ill chosen. America is just now, as

never before, posing before the world as a highly liberal and civilized nation, and in many respects she has a right to this reputation. She has brought

to her shores and given welcome to a greater variety of mankind than were ever assembled in one place since the day of Penticost. Japanese, Javanese,

Soudanese, Chinese, Cingalese, Syrians, Persians, Tunisians, Algerians, Egyptians, East Indians, Laplanders, Esquimoux, and as if to shame the Negro,

the Dahomians are also here to exhibit the Negro as a repulsive savage.

It must be admitted that, to outward seeming, the colored people of the United States have lost ground and have met with increased and galling resistance

since the war of the rebellion. It is well to understand this phase of the situation. Considering the important services rendered by them in suppressing

the late rebellion and the saving of the Union, they were for a time generally regarded with a sentiment of gratitude by their loyal white fellow

citizens. This sentiment however, very naturally became weaker as, in the course of events, those services were retired from view and the memory of

them became dimmed by time and also by the restoration of friendship between the north and the south. Thus, what the colored people gained by the war

they have partly lost by peace.

Military necessity had much to do with requiring their services during the war, and their ready and favorable response to that requirement was so simple,

generous and patriotic, that the loyal states readily adopted important amendments to the constitution in their favor. They accorded them freedom and

endowed them with citizenship and the right to vote and the right to be voted for. These rights are now a part of the organic law of the land, and as

such, stand to-day on the national statute book. But the spirit and purpose of these have been in a measure defeated by state legislation and by

judicial decisions. It has nevertheless been found impossible to defeat them entirely and to relegate colored citizens to their former condition. They

are still free.

The ground held by them to-day is vastly in advance of that they occupied before the war, and it may be safely predicted that they will not only hold

this ground, but that they will regain in the end much of that which they seem to have lost in the reaction. As to the increased resistance met with

by them of late, let us use a little philosophy. It is easy to account in a hopeful way for this reaction and even to regard it as a favorable symptom.

It is a proof that the Negro is not standing still. He is not dead, but alive and active. He is not drifting with the current, but manfully resisting

it and fighting his way to better conditions than those of the past, and better than those which popular opinion prescribes for him. He is not contented

with his surroundings, but nobly dares to break away from them and hew out a way of safety and happiness for himself in defiance of all opposing

forces.

A ship rotting at anchor meets with no resistance, but when she sets sail on the sea, she has to buffet opposing billows. The enemies of the Negro see

that he is making progress and they naturally wish to stop him and keep him in just what they consider his proper place.

They have said to him "you are a poor Negro, be poor still," and "you are an ignorant Negro, be ignorant still and we will not antagonize you or hurt

you." But the Negro has said a decided no to all this, and is now by industry, economy and education wisely raising himself to conditions of

civilization and comparative well being beyond anything formerly thought possible for him. Hence, a new determination is born to keep him down. There

is nothing strange or alarming about this. Such aspirations as his when cherished by the lowly are always resented by those who have already reached

the top. They who aspire to higher grades than those fixed for them by society are scouted and scorned as upstarts for their presumptions.

In their passage from an humble to a higher position, the white man in some measure, goes through the same ordeal. This is in accordance with the nature

of things. It is simply an incident of a transitional condition. It is not the fault of the Negro, but the weakness, we might say the depravity, of

human nature. Society resents the pretensions of those it considers upstarts. The new comers always have to go through this sort of resistance. The

old and established are ever adverse to the new and aspiring. But the upstarts of to-day are the elite of to-morrow. There is no stopping any people

from earnestly endeavoring to rise. Resistance ceases when the prosperity of the rising class becomes pronounced and permanent.

The Negro is just now under the operation of this law of society. If he were white as the driven snow, and had been enslaved as we had been, he would

have to submit to this same law in his progress upward. What the Negro has to do then, is to cultivate a courageous and cheerful spirit, use

philosophy and exercise patience. He must embrace every avenue open to him for the acquisition of wealth. He must educate his children and build

up a character for industry, economy, intelligence and virtue. Next to victory is the glory and happiness of manfully contending for it. Therefore,

contend! contend!

That we should have to contend and strive for what is freely conceded to other citizens without effort or demand may indeed be a hardship, but there is

compensation here as elsewhere. Contest is itself ennobling. A life devoid of purpose and earnest effort, is a worthless life. Conflict is better than

stagnation. It is bad to be a slave, but worse to be a willing and contented slave. We are men and our aim is perfect manhood, to be men among men. Our

situation demands faith in ourselves, faith in the power of truth, faith in work and faith in the influence of manly character. Let the truth be told,

let the light be turned on ignorance and prejudice, let lawless violence and murder be exposed.

The Americans are a great and magnanimous people and this great exposition adds greatly to their honor and renown, but in the pride of their success

they have cause for repentance as well as complaisance, and for shame as well as for glory, and hence we send forth this volume to be read of all

men.

Source: A Celebration of Women Writers, "Introduction," The Reason Why . . . by Frederick Douglass (1893):

http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/wells/exposition/exposition.html

![]()

![]()

Go to Ida B. Wells, "Lynch Law," The Reason Why . . .

Return to Musicians/Writers/Activists

Return to Site Index

![]()

![]()

Sculpture, top of page:

Adelaide Johnson's "The Portrait Monument"

(Elizabeth Cady

Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott), 1892, 1920.

Return to Nichols Home Page

Suggestions/Comments: knichols11@cox.net

Posted: 4-15-15; Updated: 4-03-19