![]()

![]()

This Page:

The Woman's Building: Sophie Hayden, architect

Woman's Building Statuary: Rideout, Yandell, Rope

Murals: Mary Cassatt and Mary Macmonnies-Low

Other Murals (Fuller, Sherwood, Emmet, Sewell, Merritt, Swynnerton)

Wall Murals, French Section (Louise Abbéma)

Library Ceiling & Interior Designs: The Wheelers

![]()

![]()

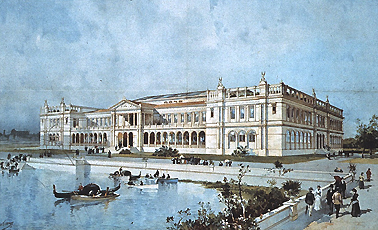

The Woman's Building by Sophie Hayden. Photo/commentary

here.

Sophia Hayden, one of the few women architects in nineteenth-century America, graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and, as her first project, designed the 80,000 square-foot, two-story building called the Woman's Building. A young woman, Hayden evidently suffered some kind of breakdown by the end of the project and never again designed a building.

Responses to the building (and to a woman architect) were mixed. The Italian Renaissance style building was considered by some viewers to be too plain and unassertive compared with the more flamboyant, male-designed buildings elsewhere at the Fair, but many women viewers felt it was "just enough." Other critics, knowing the architect's sex, thought they saw "feminine" traits like "delicacy" and "timidity" in the building's architecture. Hayden's design for the rectangular rotunda topping the Woman's Building also received some criticism, but other sources remarked on how, inside the building, it provided a marvelous source of light and radiance.

Interior of Woman's Building (Gallery of Honor).

Several of the building's murals, created by women, can be seen on the upper

levels:

Amanda Sewell's Arcadia and

Lucia Fuller's Women of Plymouth

(upper left)

and in the far distance (center) Mary MacMonnies-Low's

Primitive Woman.

In charge of this all-woman project was a Board of Lady Managers chaired by Bertha Potter Palmer, a wealthy and influential patron of the arts. Placing women in charge of their own building was considered a rather revolutionary idea at the time and was not enthusiastically supported by some Fair authorities. In addition, various women's groups, some more conservative, others more liberal, competed for control of the "message" that the Woman's Building would communicate about women. (See the Harriet Hosmer entry and links here for one example of these power struggles over her Queen Isabella statue.)

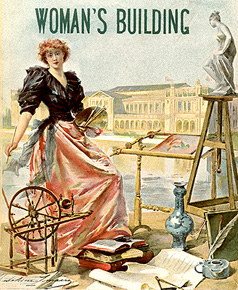

Catalog Cover

by Madeleine Lemaire

There was also some generational tension at times. Several older but well-known women's rights activists and reformers were featured as speakers at the World's Congress of Representative Women held in the Woman's Building--for instance, the famous suffragist Susan B. Anthony giving the opening address, the well-known anti-slavery advocate Lucy Stone reporting on The Progress of Fifty Years, attorney-activist Mary A. Greene discussing The Legal Condition of Women in 1692 -1892, and feminist-novelist Lillie Devereux Blake reminding the audience of Our Forgotten Foremothers. (For more details, see The Congress of Women.)

Portrait in bronze of Mrs.

Potter Palmer, President

of the Board of Lady

Managers, World's Columbian

Commission

--exhibited in the

Library, Woman's Building,

1893 Exposition.

However, some of the younger "new women" were more concerned about maintaining a more "ladylike" demeanor or, alternately, adopting a more professional tone, yet it was finally Bertha Potter Palmer, the Gilded Age matron married to a wealthy industrialist, who correctly assessed the great significance of the project of the Woman's Building--the fact that Congress had actually agreed to authorize and fund a building devoted to women. As she put it, "Even more important than the discovery of Columbus, which we are gathered together to celebrate, is the fact the General Government has just discovered women" (source).

Despite this welter of competing interests, goals, and criticisms, the Woman's Building turned out to be a successful as well as historic project as far as most participants were concerned. It housed a vast array of exhibits on women's progress from primitive to modern times in the arts, crafts, sciences, education, and labor. The Library, for instance, had 7,000 volumes of books by women (including 47 translations and editions of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin) produced between the 16th to 19th Century. As Fryer notes, "Displays ranged from the Queen of Italy's handmade lace and cigarettes rolled by Spanish women laborers to those showing increasing interest among middle-class women in technological invention and 'scientific' approaches to philanthropy: portable sinks and dish-heaters, for example, portable bathtubs and mechanical dusters, all invented by women, women's patented transportation systems, typewriters and a citywide waterworks project."

International breadth was also achieved with women's exhibits from Siberia, Siam, Japan, Norway, Austria, Germany, Belgium, Holland, India, Sweden, Italy, Spain, Brazil, Mexico, Great Britain, the Cape of Good Hope, and other countries.

![]()

from the Enlightenment

statuary group.

from the Virtues statuary

group (drawing).

Alice Rideout's twelve-foot allegorical statuary groups adorned the four corners of the roof of the Woman's Building. The "Enlightenment" group consisted of "the Spirit of Civilization holding the Torch of Wisdom." The bird of wisdom was at the base, along with a woman in cap and gown rising above a dejected woman searching for knowledge. The "Three Virtues" group had a central figure of "Innocence." At the base was the pelican symbolizing love and sacrifice, accompanied by a nun sacrificing her jewels on an altar and a woman charitably nursing two orphans.

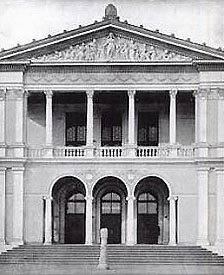

Pediment--above main entrance to the Woman's Building, 1893 Exposition.

The pediment was 45 feet long and 7 feet high at the center.

Rideout's Pediment, Woman's Building entrance.

Alice Rideout also created friezes on the 45-foot long pediment and on the panels over the doors. The images represented literature and art, various virtues such as "beneficence," and women's occupations.

Little biographical information is available online about Alice Rideout. Born in California, she was the ward of John Quinn, a well-know art collector from San Francisco. She studied at the San Francisco School of Design and by age 19 was working on a bust of President Benjamin Harrison when she was commissioned to work on statuary at the 1893 World Fair. Afterwards, she disappears from history.

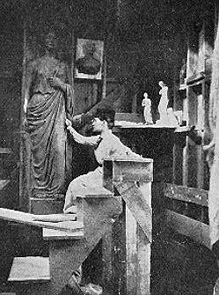

Yandell working on

the caryatids.

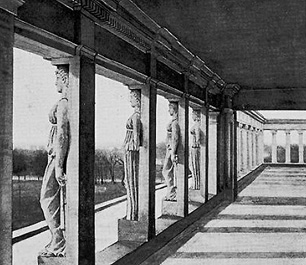

Caryatids, Upper porch,

Woman's Building.

See more information on the life and art of Enid Yandell.

Charity

[Copyright H.Blairman & Sons--http://www.blairman.co.uk/]--

one of four spandrels for the Woman's Building, 1893 Exposition.

Ellen Mary Rope designed four plaster-relief panels (6 feet tall images of "Faith, "Hope," "Charity" and "Heavenly Wisdom") for the Woman's Building at the Chicago 1893 World Columbian Exposition. For more information, see the artist and her work here.

![]()

Modern Women (mural) by Mary Cassatt--the mural opposite Macmonnies'

Primitive Women mural (see below) in the Woman's Building

at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893.

For more information on Cassatt's mural and participation in the 1893 Exposition, go to her page.

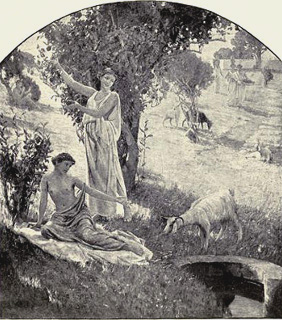

Primitive Woman (mural) by Mary Macmonnies-Low--

the mural opposite Cassatt's Modern Woman mural (view Cassatt's mural here)

in the Woman's Building at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893.

Unlike the impressionistic mural by Mary Cassatt, the "Primitive Woman" mural by Mary Macmonnies-Low at the oppositie end of the Gallery of Honor in the Woman's Building was created in a more traditional neo-classical style. Its idealized figures were more in accord with the taste of the general public that still considered Cassatt's impressionist mural to be experimental and unorthodox.

According to one report, MacMonnies-Low's mural depicted primitive women "engaged in the various industries and pursuits of her time. The scene is out of doors, with a blue lake and its bordering trees for a background." Another source claims that "the central figure represent[s] motherhood, with women on either side sowing seed and carrying jars of water."

Macmonnies-Low Links:

Three Girls in a Flat, Chap. 5 --scroll down the page.

The Book of the Fair, Chap. 11, Woman's Building

More information on Macmonnies-Low.

![]()

Women of Plymouth by Lucia Fairchild Fuller--

mural in Woman's Building, 1893 World's Exposition.

Study for the Women of Plymouth mural, plus commentary, here.

The "Women of Plymouth" mural by twenty-three year old Lucia Fuller depicted seventeen early American women engaged in daily tasks such as washing, educating children, and spinning. Although other murals commissioned for the Woman's Building at the 1893 World Fair seem to have disappeared, her Women of Plymouth was found in a deteriorating building in Cornish. One source claims that her mural was never shown at the World Fair because of the anachronistic error of showing tree stumps sawn smooth rather than roughly axed by the Pilgrims, but photos of the Gallery of Honor in the Woman's Building show her mural on the wall.

Arcadia (mural)

by Amanda Brewster Sewell.

Republic Welcomes her Daughters

(mural) by Rosina Emmet Sherwood

Art, Literature, and Imagination

(mural) by Lydia Field Emmet

Two murals hanging on wall of Gallery of Honor, Woman's Building, World Fair 1893.

Sewell's Arcadia (left); Fuller's Women of Plymouth (right).

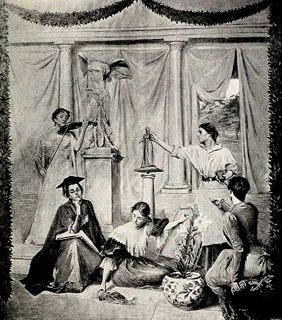

Needlework Sketch of Decoration for

Vestibule in the Woman's Building 1887--

by Anna Lea Merritt.

Both Anna Lea Merritt (American-born, but lived and exhibited in Great Britain for most of her adult life) and British painter Annie Louisa Swynnerton were asked to make large murals, presumably about "woman's work," for the east "vestibule" in the Woman's Building, but the only pictorial record remaining of them is the above sketch of Merritt's mural which one source described in this way:

The central panel is a spirited scene, representing woman the mistress of the needle. A group of seated figures about an embroidery frame is particularly worthy of notice. In the right-hand panel a group of fair girl graduates receive their diplomas from the hand of a college dignitary.

Swynnerton's mural, on the other hand, has been described as follows:

The one by Mrs. Swynnerton represents three different phases of nursing, the care of the young, the sick, and the aged. The decoration is in the form of a triptych. The central panel represents the Crimean Hospital at Scutari, with the sick and wounded soldiers lying on their pallet beds, their faces turned toward the single gracious figure of Florence Nightingale standing in their midst, a figure full of dignity and of pathos. It was in this hospital that the dying boy kissed the shadow of Florence Nightingale as it fell upon the wall by his bed. In one of the smaller panels we have a handsome, robust young mother with a lusty child upon her knee, while the remaining one shows us the figure of an aged woman; beside her sits her young granddaughter.

There were some complaints that the vestibule in which both murals were hung was so narrow that it was hard to view them--which perhaps explains why no photos were ever taken of them, as far as we know (source).

More information on Lucia Fairchild Fuller.

More information on Amanda Brewster Sewell.

More information on Rosina Sherwood.

More information on Lydia Emmet.

More information on Anna Lea Merritt.

More information on Annie Louisa Swynnerton.

![]()

France--mural

exhibited in

Woman's Building, 1893 Exposition.

France on the Way to

the Chicago

Exposition--mural exhibited in

Woman'sBuilding, 1893 Exposition.

More information on Louisa Abbéma.

![]()

Library Ceiling Mural by Dora Wheeler Keith.

According to one source, "In the central oval, enclosed by a wreath of white lilies, literature is typified by a shapely woman, science by a man in scholastic garb, and imagination by an angel with its outstretched wings. Between this oval and the Venetian border which encloses the ceiling, are loops and folds of drapery in softly blended hues representing the tints of sky and landscape, and at the four corners are medallions symbolic of history, romance, poetry, and drama." (Source)

The designer of the library ceiling was Dora Wheeler Keith, daughter of Candace Wheeler (see below). Dora was educated in New York at the Art Students League and in Paris at the Académie Julian. She won awards at the Pan-American Exposition in New York in 1886 and the Louis Prang Prize for greeting card designs in 1885-6.

Supervising the interior decorations of the Woman's Building was Candace Wheeler, mother of Dora Wheeler Keith and the most important textile and interior designer of the Nineteenth Century. Inspired by the embroideries she saw at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Wheeler professionalized the role of women in decorative design by founding the Society of Decorative Art in New York and the Women's Exchange, a self-help organization which taught women applied arts and thus gave them a means of economic independence. After a period of time with the Tiffany Company producing designs for prestigious clients such as the White House and Mark Twain, Wheeler developed Associated Artists, an all-women design firm in New York (1883-1907). Her textile designs, practical and affordable for middle-class women, were often based on American plants and flowers.

Wheeler also wrote books on botany, gardening, and art. See The Dream City--Candace Wheeler article on the 1893 World Fair in Harper's New Monthly Magazine LXXXVI.516 (May 1893): 830-846.

![]()

![]()

Carr, Carolyn Kinder. "Mary Cassatt and Mary Fairchild MacMonnies: The Search for Their 1893 Murals." American Art, 18 (Winter 1994): 53-69.

Chalmers, F. Graeme. Women in the Nineteenth Century Art World. Westport 1988.

Elliott, Maud Howe, ed. Art and Handicraft in the Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition. Rand, McNally, 1894.

Fryer, Judith. Felicitous Space. U of North Carolina Press 1986, pp. 23-6.

Galvin, Paul V. World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. Library Digital History Collection, Illinois Institute of Technology.

The Women's Pavilion--by Anne Barrows.

The Woman’s Building and the World Exhibitions: Exhibition Architecture and Conflicting Feminine Ideals at European and American World Exhibitions, 1873 – 1915--by Mary Pepchinski.

Spheres of Influence: The Role of Women at the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 and the San Francisco Panama Pacific International Exposition of 1915--article by Susan Wels.

The Book of the Fair: The Woman's Department--detailed description of every aspect of the Woman's Building.

Tour the Fair--short description, including a paragraph on Woman's Building.

Weimann, Jeanne Madeline. The Fair Women. Chicago 1981.

World's Columbian Exposition. World's Columbian Exposition, 1893 : Official catalogue : pt. XIV, Woman's Building. Chicago 1893.

Yandell, Enid, Jean Loughborough, and Laura Hayes. The Board of Lady Managers--Ch, 5, Three Girls in a Flat (1892), pp. 53-82; a first-hand report on the planning, governing, and exhibitions in the Woman's Building.

![]()

![]()

Go to Women's Public Arts & Architecture: State Buildings, p. 2

Return to White City

Return to Site Index

![]()

![]()

Text written by K. L. Nichols

Painting, top of page: Frances C. Jones,

Eastern Veranda of the Woman's Building Looking

toward

the Illinois Building, World's Columbian Exposition (1893)

Return to Nichols Home Page

Suggestions/Comments: knichols11@cox.net

Posted: 6-25-02; Updated: 12-22-17