![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Say not, "Greece is no more."

Through the clear morn

On light winds borne

Her white winged soul sinks on the New World's breast.

Ah! happy West--

Greece flowers anew, and all her temples soar!

from "The White City" (1893) by Richard Watson Gilder

Make it bigger and better than any that have preceded it. Make it

the GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH.

from "What the Fair Should Be" (1890) by P.T. Barnum

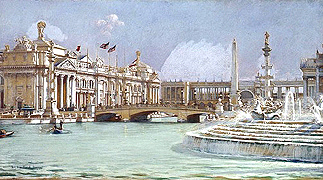

Costing over a half billion in today's dollars and covering 686 acres, the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition and Fair in Chicago was a grand sight to its 27 million visitors--a planned layout of large, classically-inspired buildings (what we now call the "Beaux Arts" style) all built on the same scale and all painted white--hence, the nickname of "The White City" or "The Dream City." And within and around those white buildings was the most amazing display of 65,000 exhibits depicting (to quote the Exposition promoters) "all of the highest and best achievements of modern civilization; all that was strange, beautiful, artistic, and inspiring; a vast and wonderful university of the arts and sciences, teaching a noble lesson in history, art, science, discovery and invention, designed to stimulate the youth of this and future generations to greater and more heroic endeavor" (The Dream City, publisher's introduction, 1893).

The Machinery Building, World's Columbian Exposition,

1893 by Lewis Edward Hickmott. The

neo-classic

buildings surround the Grand Basin (reflecting pool)

in the Court of Honor at the center of the White

buildings--see photo and

more photos.

Daniel Chester French's gilded "Statue of the

Republic"

in the Court of Honor by Charles

Courtney Curran. Peristyle and arch in back-

ground are also decorated with

statues.

A Night in the Grand Court (lit by that exciting,

new invention called electric lights)

by Charles S. Graham.

Dream City, indeed! That wasn't just advertising hype as far as many fairgoers were concerned. "Sell the cook stove if necessary and come. You must see this fair," exclaimed the writer Hamlin Garland in a letter to his parents back in Dakota (source). Western writer Owen Wister was nearly stuck dumb with admiration: "Before I had walked for two minutes, a bewilderment at the gloriousness of everything seized me ... until my mind was dazzled to a stand still" (source). Even Theodore Dreiser, the naturalistic writer of Chicago's urban realities, was overcome with idealistic awe:

I have often thought since how those pessimists who up to that time had imagined that nothing of any artistic or scientific import could possibly be brought to fruition in America, especially in the middle West, must have opened their eyes as I did mine at the sight of this realized dream of beauty, this splendid picture of the world's own hope for itself. . . . It was . . . as though some brooding spirit of beauty, inherent possibly in some directing over-soul, had waved a magic wand quite as might have Prospero in The Tempest or Queen Mab in A Midsummer Night's Dream, and lo, this fairyland. (Dreiser, A Book about Myself, p. 246).

The Bard's magic infused with a big dose of Emersonian transcendentalism. What more could visitors wish for!

Art Palace at Night, (currently Chicago's

Museum of Science and Industry)

--by Charles S. Graham.

Frederick MacMonnies' Columbian Fountain

and Barge of State in the Grand Basin of the

Court of Honor by Mary MacMonnies.

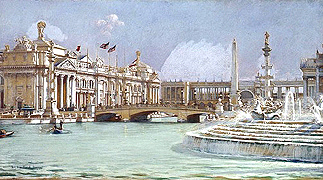

Supposedly the fair was held to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492, and his long voyage was represented by the large pool of water at the center of the Court of Honor. However, many other cultural, technological, and economic interests were also competing for attention at this grand event.

The Landing of Columbus in the New World

--1892 Commemorative U.S. Stamp, 2 cents.

Based on John Vanderlyn's painting "Landing of

Columbus" which was commissioned by Congress

in 1836 and installed in the capitol rotunda in

1847.

This world's fair was particularly important to the late-nineteenth century American art world. With about 10,000 artworks on display, it was the largest exhibition of art ever held in the United States. Having made rather poor showings in earlier international expositions, America was especially eager to establish itself as a significant force in the art world. The art exhibition, as a whole, was divided into three parts: contemporary American art (art since 1876), nineteenth-century European art from private collections in America, and a retrospective exhibition of late eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century American art.

The Horticultural Building, World's Columbian

Exposition, 1893--by Childe Hassam.

World's Fair, Chicago, 1894--by Childe Hassam.

For women painters, women sculptors, and women's architectural arts, the opportunity to exhibit to large national and international audiences was unprecedented, and the exhibition records read like a "Who's Who" of late-nineteenth century women artists, ranging from major artists with established trans-Atlantic reputations, like American expatriate Mary Cassatt or French artist Rosa Bonheur, to women artists with more local or regional reputations within the U.S. or their countries of origin. In fact, the more generous inclusion of women's art in 1893 (limited as that was) set a precedent for later expositions.

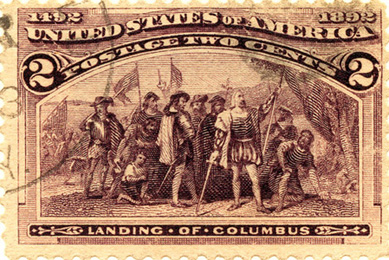

Electrical Building Interior

by Charles S. Graham.

For many awestruck visitors, the grand displays of art and other examples of American industrial, cultural, and technological accomplishment were a source of national pride: "By displaying the diverse forces that'd made us, it drew us together and helped shape a national identity. It reminded us of what we wanted to be. No wonder poet Katherine Lee Bates visited the fair and then went home to write America the Beautiful. The startling thing about that was her phrase, 'Thine alabaster cities gleam.' For that line described the pavilions of the fair far more accurately than any existing American city!" (source).

Mixed in with all the sights at the fair was music of every kind,

ranging from performances of the famous New World Symphony composed for the occasion by Czech composer Antonín Dvorak to crowd-pleasing marches

by John Philip Sousa's band, improvisations of "The Star

Spangled Banner" on a super-sized pipe organ with 3,901 pipes built especially for the fair, and a giant marimba featured in the Guatamalan Building,

among the many choices.

It was a heady experience for many fair-goers. Inspired by the 'White City,' L. Frank Baum wrote about a fabulous Emerald City in The Wizard

of Oz. To advocates of "the city beautiful" movement, which hoped

to encourage moral and civic virtue through urban beautification, the "White City" would become the model for city planning in Washington,

D.C. and for public buildings in general for at least the next fifty years

(source-1 and

source-2).

Others viewed the 1893 Exposition as a celebration of the new consumer society ushering in the Twentieth Century. At a seminar held at the fair, historian Frederick Jackson Turner would announce his famous thesis on "The Significance of the American Frontier in American History"--namely, that it disappeared in the early 1890s. As one source noted, "America's transformation from a society of farms and owner-operated businesses at the start of the 1800s to the industrialized, corporate-controlled urban society" was becoming evident to many: "The exposition ushered in a new age of consumerism with introduction of brand names -- Cream of Wheat, Shredded Wheat, Pabst Beer, Aunt Jemina's syrup and Juicy Fruit gum-- destined to become as much a part of Americana as the Ferris Wheel, carbonated soda and hamburger, which also were popularized at the fair" (source).

Souvenir items, like these coins honoring Columbus' "discovery"

of America, were good money-makers for the Fair sponsors.

(Left) Queen Isabella, designed by Caroline Peddle Ball;

(Right) Columbus, designed by Auguste Saint-Gaudens.

However, more skeptical voices could also be heard. One source noted that the Exposition's popularity may have had more to do with the Midway Plaisance which was a cross between a carnival and a kind of nineteenth-century Disney World theme park: "While the public may have been awestruck by the grandeur of the architecture and impressed by the array of consumer products, what kept them at the fair was the Midway Plaisance, a commercially-sponsored self-contained amusement area. It featured popular entertainment such as German beer halls, the original Ferris Wheel, Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show and exotic dancers" (source).

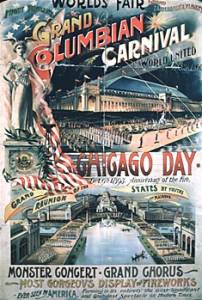

Poster advertising

"Chicago Day" with

a grand chorus and

carnival with

fireworks.

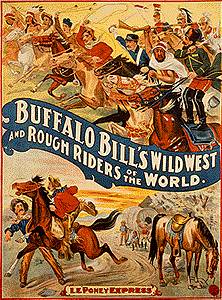

Poster announcing

Buffalo Bill's Wild

West Show starring

both Indians and the

Rough

Riders.

Charles C. Graham's

painting of Little

Egypt doing the

hootchy-kootchy to

The

Snake Charmer

song.

Kyleopatra (39 in. tall)--

by J. Koenig and Uriel

Plaster Co--sold in

Egyptian

Pavilion on

"A Street in Cairo."

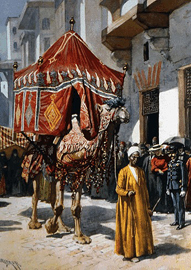

Camel Ride by Bror

Thure de Thulstrup.

A popular tourist

attraction on

"A Street in

Cairo."

The "theme park" quality of the Midway was due partly to the international focus of a number of the displays which were geared more toward tourism rather than anthropological study.

The international exhibits "could be categorized into two groups: the first was a stereotypical parody of a culture, a sort of caricature of the host country it represented, displayed as little more than a side show. This was especially true for cultures that were generally the subject of bias and underrepresented to begin with. There was a Dahomey village from 'darkest Africa' which showed the 'cannibal tribe'. Indian 'chiefs' and 'braves' in feathered headdresses also were put on show, set into an environment of teepees and wigwams. The second category of international display was a bit more realistic and at least as legitimate as one could get at the Midway. These included the German beer halls, the noisy Egyptian bazaars, the controversial Algerian belly dancers, and the World Congress of Beauties, which showed representatives of forty countries in national attire."

As one critic put it, "The most obvious reason for the popularity of the Midway was its very purpose. Despite the numerous, novel exhibits of the main Fair, the Midway's ' "Barnumesque eclecticism" and exuberant chaos' . . . was simply designed to entice crowds with its bright lights and happy sounds."

To another critic, it functioned as "a valve that allowed visitors to relax and enjoy the Exposition without any pressure to 'keep up' ". (source)

But for many visitors, the mechanical wonder of the giant ferris wheel towering above the Midway was the best emblem of modern American technology merged with

entertainment that the Fair offered--and vastly superior to the French Eiffel Tower revealed at the 1889 world's fair in Paris.

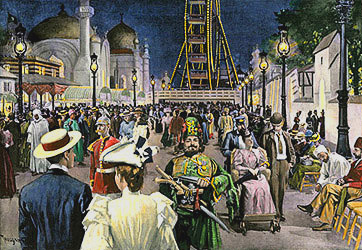

Visitors Enjoy the Midway at Night

by Bror Thure de Thulstrup.

Even more serious criticism of the Exposition was offered by an up-and-coming American architect with new ideas about the future of American identity and architectural design. Louis Sullivan, inventor of the skyscraper and designer of the Exposition's Golden Doorway (see below), described the influence of the Beaux-Arts architecture at the fair as a contagious virus and offered the following, oft-quoted prediction:

The virus of the World’s Fair, after a period of incubation in the architectural profession and in the population at large, especially the influential, began

to show unmistakable signs of the nature of the contagion. There came a violent outbreak of the Classic and the Renaissance in the East, which slowly spread westward,

contaminating all that it touched, both at its source and outward. . . .

The damage wrought by the World’s Fair will last for half a century from its date, if not longer. It has penetrated deep into the constitution of the American mind,

effecting there lesions significant of dementia. (source)

Strong language, indeed! To innovative architects like Sullivan and his draftsman Frank Lloyd Wright, the White City was America's tribute to its Old World past rather than to its New World future. Sullivan's colorful design for the Transportation Building with its prominent "Golden Doorway" was a deliberate repudiation of the gleaming white Beaux-Arts style of the Court of Honor buildings. The French Commissioner of Decorative Arts, André Bouilhet, would later declare that it was the only "truly original " building at the Fair. He added, "and it has the special merit of recalling no European building" (source).

The Transportation Building, World's

Columbian Exposition 1893 by

Frank Russell Green. This "Golden

Doorway"

designed by Louis Sullivan

broke with the neoclassic standards

of the White City.

The Water Gate, World's

Columbian Exposition,

1893 by Charles Courtney

Curran. Typical Beaux-Arts

or

neo-classical style.

Chicago World's Fair

(1894)

by Thomas Moran

Other critical voices were heard from women activists lamenting the exclusive image of bourgeois femininity promulgated by the

Woman's Building and other exhibits

(source).

Racial minority groups pointed out how "white," in terms of race, the "White City" really was. Unfortunately, there was no

satisfactory answer to give to Ida B. Wells' question: "Why are not the colored people, who constitute so large an element of the American

population, and who have contributed so large a share to American greatness, -- more visibly present and better represented in this World's

Exposition?" (source) Many working-class people and social

reformers also objected to the upper middle-class elitism of the Exposition in contrast to the social problems of the inner city (crowded slums,

poverty, unemployment, crime).

In the following links, some fair-goers expand on the various meaning(s) they attributed to the Columbian Exposition in the 1890s: Capitalism or aestheticism or national identity (Henry Adams; William Dean Howells; Julian Hawthorne; Frederick Jackson Turner); the missing racial minorities (Frederick Douglass; Ida B. Wells; Paul Laurence Dunbar; Simon Pokagon); and the feminist/suffragist speakers and writers (Susan B. Anthony; Elizabeth Cady Stanton; Marietta Holley).

Despite the variety of opinions--or perhaps because of them--the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition and Fair in Chicago was one of the great cultural events of the Nineteenth Century--not to be missed, whether the viewers loved it or quarreled with it. It made art history, set attendance records, boosted national pride, and signaled the United States beginning to emerge as a world economic and technological power.

* * *

For more on the impact the Exposition had on American culture and self-perception, see The Legacy of the Fair. An in-depth study of the contradictory meanings of the 1893 Exposition can be found in Chapter 7: The White City in Alan Trachtenberg's book The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age.

![]()

![]()

Go to More White City Paintings, Part 1

Return to Site Index

![]()

![]()

The Advent of the 'Nigger': The Careers of Dunbar, Tanner, and Chesnutt--see especially the first section "Pretext: Chicago World's Columbian Exposition as Racial Locus."

The Literary Reception of the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition, 1893"--dissertation. (Howells,Burnett, Burnham, van Deventer).

World's Columbian Exposition: Idea, Experience, Aftermath--excellent site with many links; very readable.

World's Columbian Exhibition--photo tour.

Photos of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition

World's Columbian Exposition of 1893--probably the longest and most detailed study online; many, many links.

World's Columbian Exposition of 1893--Paul V. Galvin Library Digital History Collection.

1893 Exhibition--note on "America the Beautiful" being written in response to the "White City."

The White City and After--1905 article on city planning and the unique qualities of the Exposition.

The White City--from essay on history of Chicago and city planning; click on links for rest of essay.

Louis Sullivan: World's Columbian Exposition--Sullivan's comments on the architecture.

Black Presence at White City--participation of blacks in the World Fair.

Frederick Douglass' Speech in Chicago--lecture on Haiti given at the Haitian Pavilion.

Colored Americans Day at the World’s Fair 1893--covers the disagreement among black leaders about "Colored American Day"; excerpt from Frederick Douglass' speech.

The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition--pamphlet of essays by Ida B. Wells and other Black writers handed out at the 1893 World's Fair.

A People without a Nation--excellent article on the absence of African-Americans at the Fair by Barbara Ballard and published in Chicago History.

Cultural and Racial Stereotypes on the Midway--excellent article by Josh Cole.

The International Strategy of African American Women at the Columbian Exposition and Its Legacy:Pan-Africanism, Decolonization and Human Rights--academic article by Elisabetta Vezzosi on the debates about Black women at the fair.

Bibliography: World's Columbian Exhibition, Chicago 1893--long and excellent bibliography of print articles and dissertations.

Woman's Political Future--the speech delivered by Frances E.W. Harper at the World's Congress of Representative Women at the Chicago World's Fair.

Stereotypes and Misconceptions of Pan-Arabic Culture at the Columbian Exposition--good thesis on racial biases.

Forms of Representation and the Redefining of Chicago at the Fin-de-Siecle--scholarly article on Chicago World Fair of 1893; includes comments on reformer Jacob Riis, artist Childe Hassam and Sister Carrie..

Posters and Book Covers--advertising art for the 1893 World Fair.

Spheres of Influence: The Role of Women at the Chicago World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 and the San Francisco Panama Pacific International Exposition of 1915--article by Susan Wels published in The Journal of San Francisco State History Students, 1999.

Parables of Stone and Steel: Architectural Images of Progress and Nostalgia at the Columbian Expositionand Disneyland--article by Michael Steiner published in American Studies 42.1 (Spring 2001): 39-67.

The Incorporation of American: The White City--Alan Trachtenberg's detailed discussion of the White City's themes.

The Dream City--an 1893 article in Harper's by Candace Wheeler, interior decorator for the Women's Building. Images included.

World's Columbian Exposition (The Midway)--PBS presentation.

World's Columbian Exposition. The official directory of the World's Columbian exposition, May 1st to October 30th, 1893. [microform] A reference book of exhibitors and exhibits, and of the officers and members of the World's Columbian Commission. Chicago 1893.

World's Columbian Exposition (1893 : Chicago, Ill.) --created search; many "official" links included.

Online Books Page: World's Columbian Exposition (1893 : Chicago) --long list of online books about the exhibitions, buildings, history, activities, etc., of the 1893 World's Fair.

Digital Books Index: 1893 World's Columbian Exposition --another long list of sources on the 1893 World's Fair.

Official Catalogue of the Illinois Woman's Exposition Board--details about the art and other exhibits in the Illinois State Building at the 1893 World's Fair.

World's Fairs and Expositions: Material Relating to World's Fairs from 1851 onward--long list of Fair sources.

The World's Columbian Exposition Illustrated Vol. II, Mar. 1892 - Mar. 1893 (Chicago, 1893)--monthly journal covering the progress of the Chicago World's Fair and Exposition.

![]()

![]()

Text written by K. L. Nichols

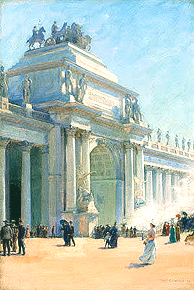

Painting, top of page: Lydia Field Emmet,

World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago (1893)

Return to Nichols Home Page

Suggestions/Comments: knichols11@cox.net

Posted: 6-25-02; Updated: 4-07-19